In my post, “You Don’t Have to Like Your Priest”, I built on Brother Patrick’s essay to describe some of the reasons that people don’t like their Orthodox priests, making the general point that all of his foibles pale in comparison to the One Thing Needful which He serves and shares. Another dynamic of this relationship is the attitude of the priest towards the people he serves. Sometimes priests have a hard time liking them, too.

The complaints priests have about difficult parishes and parishioners are legion. As with complaints of the laity about their priests, some are so well-founded as to brook nothing but sympathy and support. My last essay was not meant to excuse the kind of abuse that wicked pseudo-startsi (pseudo-elders), would-be gurus, narcissists, predators, and psychopaths inflict on parishes; nor will this one excuse the intentional physical, emotional, and financial damage that far too many parishes intentionally inflict on their priests. Those are terrible outliers and it is the responsibility of deans, bishops, and all good people to step in, stop the behavior, and heal the damage.

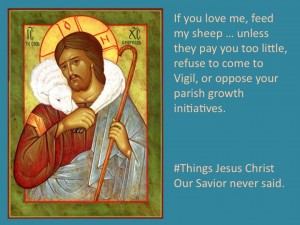

This blog post is not about cases like those (although it should be noted that one of the tactics people use is to demonize their priests/parishioners as if they were “terrible outliers”). It is about some of the temptations most parishes offer most priests much of the time.

Money.

This is a touchy subject among priests, and it won’t apply to all of them. If you’ve ever worked at a job where they asked for perfection (in this case, this can include requiring a graduate degree, bilingualism, and always-being-on-call, plus the normal PR, management, teaching, preaching, singing, etc.) but paid less than the market suggests it should, less than you expected, or less than your family needs, then you know how it can affect your attitude towards the one who signs your checks. Given that the one who signs the check is also the one that the priest serves, perhaps a better comparison would be with the waiter who relies on tips. The resentment that foments within that part of the service industry is legendary. Priests are not immune from that temptation, as sometimes it is too much for them.

I suspect that it is most tempting for priests that are trying to serve “full-time” for a parish that pays them well below the national median income while dues (!) are kept really low. The logismoi that can obsess the struggling priest’s mind compares 1) the huge sacrifices and financial opportunity costs that he and his family are incurring to serve a parish that is not their own with 2) the relatively minor financial costs parishioners are willing to incur for “their own” parish. Throw in the tons of fun when some priests get to hear their boards and members argue about why they do not merit a cost of living adjustment (much less a raise), the indignities of being treated as an employee (in a dysfunctional and oppressive corporation, no less), and the stresses of fiscal household austerity, and you have a great recipe for resentment. Because priests have learned a lot of big words, they will be tempted to voice their frustration with words like “tithing”, “stewardship”, “trebi” and “cheerful giving.” These are great words, but not if they are used out of aggravation or with a desire to extort additional revenue.

The other side of the coin is how dependent full-time priests are on their parishes. When done well, this can be a beautiful icon of our Corporate (i.e. embodied) Church where each member supplements the other, but we have all seen parishes where priests were so concerned about keeping their worldly masters happy that they soft-pedaled the Gospel. This happens to poverty-stricken priests just getting by thanks to the provision of rectory and to well-numerated priests with parish cars and a generous housing allowance.

An obvious solution to this problem is one that the economy and mission-planting has already made a necessity in many places: priests who have secular jobs and/or priest-wives who work outside the home. The scriptures bless both models of priestly service so it’s best not to get moralistic or theological either way; but there is no doubt that the priest who has a way to pay the bills without any help from his parish will generally find it easier to serve without reservation. The fact that it removes a source of leverage from less-than-scrupulous boards doesn’t hurt. Personally, I have a supportive board and parish, but the fact that I could leave tomorrow without destroying my family keeps certain temptations from even making anyone’s radar. Making ordinations of men under thirty the exception (per Canon law) would help as there are fewer situations more fraught with danger than sending a newly married young man straight of seminary with no savings, a ton of debt, and no professional job experience to lead a parish (extra points if he and his wife are new immigrants).

Parochialism/Nationalism.

This one seems especially difficult for convert clergy serving in “ethnic” Churches and parishes, but it is common enough outside of those circumstances to warrant general consideration. Each parish contains the fullness of the faith, but parochialism takes this one (unhealthy) step further when the religious/spiritual life of parishioners becomes completely defined by their specific parish. Such people rarely if ever visit other parishes; not when they go on vacation, not when they visit friends and family, not for sister parish feast days, and not for Pan-Orthodox services. The local parish is THEIR parish, with all the attitude towards control, visitors, “new” members (some of whom have been active there for decades), and priests (see “new members”) that this implies. This attitude is not theologized, it is instinctive, visceral, and tribal.

Why is this a temptation for priests – since when is loyalty a vice? It’s a reasonable question. Certainly reframing negatives into positives is part of being charitable, and loyalty is an accurate and more generous way to describe most of the parochial impulse.

The parochialism of some parishioners is a temptation for many priests because it is at odds with their own approach to the faith. The parish they serve is not “theirs” in the same way that it is for parochial parishioners. They grew up in another parish, served at another altar during seminary, and probably served an apprenticeship at another. It brings him great joy to experience the universality of Orthodoxy; so much joy that he may assume that it is required for one to really BE Orthodox. This tension can be really beneficial: a parochial parish and a priest who demands loyalty can easily combine to create a cult.

The situation of convert clergy in “ethnic” parishes is even more stark. The convert priest has given up lands, and family, and friends in pursuit of Christian perfection through Holy Orthodoxy. His experience of Orthodoxy is not rooted in any Old World culture. He may enjoy the Old World food, the Old World music, the Old World History, and the Old World Language, but it will never be his own and he will never it feel it the way many of his parishioners do. A wise monk-priest mentor once quipped; “nothing is more likely to make me an English patriot than serving [his ethnic parish]!” Whereas the convert priest has given up his own nation for Christ, the nationalist’s experience of Orthodoxy is so rooted in his national culture and experience that he cannot conceive of or enjoy his relationship with Christ outside of it. In many parishes, the convert priest is serving some people who would consider his actions traitorous had he been of their ethnicity and who will never fully consider him and his family as real members of their parish/Church.

This is an interesting mix, full of opportunities for judgmentalism and demonization. The arguments of the priest will seem more righteous because he has learned all the right words, but since when is experiencing Christ within your own culture a sin? Yes, it can go too far; busts of and tributes to Shevchenko belong in the hall, not the temple – but is there any doubt that they belong there? One of the beauties of Orthodoxy is that it blesses particular cultures, bringing them into the universality of the Church without sacrificing their unique charisms. I worry about priests who want to have a uniquely American Orthodoxy but do not recognize the validity of other organic expressions of it. It’s not always easy (I know, I am a convert priest in an ethnic diocese), but charity and patience will go along way in heading off any real problems.

Lack of Commitment.

On social media and during their late night gripe sessions, priests usually focus on the outlier parishioners who relish making their lives difficult. But the truth is that these people are not the major cause of clergy dissatisfaction with their parishes and ministry. The biggest challenge to priests is dealing with the apathy of those whom they serve. Priests are largely drawn from a population of men who love to worship, pray, fast, and learn about the faith. Again, they assume that this is the best attitude for the Orthodox Christian to have, and if he cannot have it, he should just buckle down and go through the motions until it becomes natural. He has a hard time with parishioners who rarely come to Confession or Communion, never come to classes, Vespers, or Feasts (except Nativity and Pascha), and who seem to look for excuses to miss church on Sunday. He may be able to understand the competing pressures for their time, but theologizes the situation in ways that assume such parishioners are lukewarm in their commitment to the parish, Christ, and Holy Orthodoxy.

It is true that some people lack commitment. It’s endemic to our culture (look at the divorce rate!). But these parishioners are people who could do anything on Sunday and chose to worship God. They don’t love the Liturgy the way the priest does, and yet they come. Yes, they could come more often. Yes, they could pray more. Yes, they could take the time to learn more words to describe The Way of Salvation in Christ. One day, maybe they will; but until then, they continue to come, just like they and their ancestors have for generations. If the priest is lucky, the 10%, 90% rule (10% of the people do 90% of the work) will give him enough workers (God bless our kitchen staffs!), chanters, and evangelists to do what needs to get done to sustain and grow the parish. But if he is smart, he will not pit the two groups against one another. Instead he will provide more opportunities for the 90% to get involved. This takes throwing a lot of spaghetti against the wall, but eventually some of it will stick. In the meantime, priests have to avoid the temptation of seeing such folks as the enemy or part of the problem; they could do anything – but they come!

A gatekeeper’s skill at protecting the parish during attacks can actually get in the way at other times.

The Gatekeepers.

Gatekeepers are the parishioners from the established power-families whose mission in parish life is to sustain and protect the status-quo. When priests try to change anything, the gatekeepers instinct is to either opt-out (as when they deem the change is harmless), or oppose it. When they oppose it, they rarely do it openly except as a last resort. More likely, they will resort to passive aggressive behavior and covert coalition building to undermine the change’s impact. This can be really frustrating. The irony is that when they actually buy-in to something, gate-keepers are the priest’s best ally. But for the priest who is trying to help the parish recover from decades of decline and bring growth, it gets old quickly. Trying to get gatekeepers to support initiatives can turn the priest into a politician, a role he may not enjoy or feel is meet and right for someone in his position. One alternative is to remove the power-players from the kinds of institutional positions that allow them to exercise power. Unfortunately, this is the kind of move that can easily destroy a parish – not to mention the priest’s tenure. Games like that turn potential allies into enemies who will use their influence and networks to make the priest’s life miserable and his time at the parish as short as possible. This need not happen.

Priests have to remember that the gatekeepers see themselves as guardians of the parish, and often for good reason. Many have helped the parish weather a procession of bad priests, economic downturns, schisms, and all kinds of other challenges. No one should doubt their love for the parish for a second; what kind of leader cannot work with people who have that kind of devotion? It may take time to build their trust, and there is no way (short of ceding pastoral responsibility) to keep from upsetting them at some point. But if the priest can convince them of his love for the parish and his ability to improve the chances of its survival, then he will have a partner in his ministry. I am not completely naive. Of all the challenges, the gatekeeper is the hardest one to deal with, but if a person who genuinely loves the parish and is willing to work for its survival is the worst challenge a priest faces – shouldn’t he really consider himself blessed?

They are Broken.

While there are tools like charity and patience that will help priests deal with the problems in their parishes, the most important thing is to remember that parishioners are broken people in need of the Good News. It is through the priest that this healing is offered. He serves in imitation of the Christ, the one who was Himself mistreated for doing nothing but bringing salvation to suffering people. In the end, it is the kenotic Cross of Christ – not the adoration, support, or likability of fallen men – that is the mechanism of our salvation. And if the priest is willing to join St. Paul and all the saints in being crucified with Him on that Cross, then there is no one that can hurt him and no one he cannot love.